In my previous post, “Kiko’s Passover Problem, Part I”, I showed that Kiko Arguello deforms the meaning of the Last Supper and Jesus’s death by stripping the sacrificial element out of the Jewish Passover of first century Palestine. This causes a problem for Kiko because Jesus considered himself to be the sacrificial Lamb of the New Passover, as did the inspired authors of the New Testament.

In a catechesis associated with the final convivence of the Neocatechumenal Way’s initial catechesis, Kiko teaches,

Was it that God, like a kind of Moloch, was placated and satisfied with the sacrifice, with the blood of his Son? If so, what sort of God have we made for ourselves? We have arrived at thinking that God, like the pagan gods, satisfies his anger with the sacrifice of his Son. This is why it is normal for the atheists to say: what kind of God is this who discharges his anger against his Son on the cross? And what could we answer? Certain juridical and clumsy rationalizations of the theology of expiation and the Eucharist have brought us to these deformations, to believing in a “God whose ruthless justice would have demanded a human sacrifice, the immolation of his own Son.”[1]

I have two problems with Kiko’s statement, and in the remainder of this post I’d like address those problems, and in doing so, explain why the sacrificial nature of Jesus’s death is so important.

The Strawman Argument

My first objection to Kiko’s statement is that he is attempting to deny the sacrificial element of Jesus’ saving death by using a “strawman” argument. That is, he’s deliberately presenting Catholic teaching in a way that he can easily knock down to convince his listeners of his non-sacrificial view of Jesus’ death. Kiko creates this “strawman” in two ways. First, he presents a word picture of an angry, vengeful God, one with a nasty temper like ourselves. Look at the phrases he uses, “satisfies his anger”, “discharges his anger”, and “ruthless justice”. To be sure, the Sacred Scriptures, even books in the New Testament, discuss God’s “wrath”, but this wrath should be seen as God’s passion for holiness and for making things right, and His “wrath” is not at all like a human temper tantrum.[2] Secondly, he deliberately presents a flawed view of the Holy Trinity, or rather, he ignores the dynamics of the Trinity altogether by excluding the possibility that Jesus is both the priest (offerer) and the victim of the sacrifice of the passion and that His sacrifice on the cross was a self-offering, and that offering was made in the furnace of love that is the Holy Trinity.

“Juridical and Clumsy Rationalizations”

In addition to Kiko’s “strawman” approach, I take issue with his statement, “Certain juridical and clumsy rationalizations of the theology of expiation and the Eucharist have brought us to these deformations.” With these words, Kiko pits himself against several saints, including four Doctors of the Church. The dominant theories of the atonement in Catholic theology were taught by Church Fathers such as St. Irenaeus, and St. Gregory of Nyssa, and by Doctors of the Church such as St. Augustine, St. Anselm, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, and St. Thomas Aquinas. These men reflected prayerfully on the atonement and built upon the reflections of saints before them. Our Church, you see, is no longer an infant Church, a Church in diapers, but rather has been fruitfully reflecting on the mystery of Christ’s passion for twenty centuries. It’s doctrines develop organically over time.

Let’s take a look at these “juridical and clumsy rationalizations” and the men Kiko Arguello accuses of engaging in them.

The Ransom Theory

Some of the earliest explanations for the efficacy of Jesus’s sacrificial death come from St. Irenaeus of Lyons (d. circa 202 AD), and Origen (died 254) who concentrated on Christ’s death as a “ransom”[3], as is attested to in the Sacred Scriptures.[4]

The Entrapment Theory

It became obvious to subsequent Church Fathers, such as St. Gregory of Nyssa (335-395 AD) and St. Augustine (354-430), that the scriptural figure of “ransom” could only be taken so far. After all, who would receive the ransom? The devil? And if so, how could the infinitely good God owe the devil anything?

St. Gregory of Nyssa’s response can be found in his work, The Great Catechism, in which he describes the incarnated body of Jesus acting as “bait” on the “hook” of the Deity:

“In order to secure that the ransom in our behalf might be easily accepted by him who required it, the Deity was hidden under the veil of our nature, that so, as with ravenous fish, the hook of the Deity might be gulped down along with the bait of flesh, and thus, life being introduced into the house of death, and light shining in darkness, that which is diametrically opposed to light and life might vanish; for it is not in the nature of darkness to remain when light is present, or of death to exist when life is active” (XXIV). [5]

St. Augustine, a Doctor of the Church, also proposed the notion

that the death of Christ on the cross was a trap for the devil when he taught,

“But the Redeemer came, and the seducer was overcome. And what did our Redeemer do to him who held us captive? For our ransom he held out His Cross as a trap; he placed in It as a bait His Blood. He indeed had power to shed His Blood, he did not attain to drink it. And in that he shed the Blood of Him who was no debtor, he was commanded to render up the debtors;”[6]

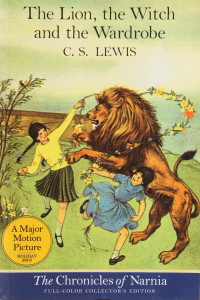

By the way, if you’ve read C.S. Lewis’s famous story, “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe”, you probably can recognize St. Augustine’s explanation in the narrative when the White Witch executes the Christ-figure Aslan in the place of the treacherous Edmund on the Stone Table. The witch rejoices over what she assumes is her “victory”, but her gloating turns to horror when Aslan rises from the dead and she realizes that she unwittingly undid the dark magic that held the land of Narnia for so long.

By the way, if you’ve read C.S. Lewis’s famous story, “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe”, you probably can recognize St. Augustine’s explanation in the narrative when the White Witch executes the Christ-figure Aslan in the place of the treacherous Edmund on the Stone Table. The witch rejoices over what she assumes is her “victory”, but her gloating turns to horror when Aslan rises from the dead and she realizes that she unwittingly undid the dark magic that held the land of Narnia for so long.

The Satisfaction Theory

St. Anselm of Canterbury (1033 – 1109), a Benedictine monk and Doctor of the Church, is famous for his Satisfaction Theory of the Atonement.[7] The International Catholic University’s “Christology” course text explains St. Anselm’s Satisfaction Theory of the Atonement well:

“When man offended God by disobeying his commandments, he offended against the infinite dignity of God. Thus it would take an infinite amount to satisfy for this infinite offense. After sin, man owes God an infinite amount of satisfaction, but man being finite cannot pay such an amount. And because man has already disobeyed God, he cannot even give to God everything that he could have given to God; he can no longer give sinless life. Only an infinite God could provide the infinite satisfaction. Only a man can satisfy since he caused the offense. The only solution therefore is a God-man who as God can provide infinite satisfaction and as man can satisfy for man’s offense.”

Peter Abelard (1079-1142) held that Christ’s death for our salvation was not expiatory, but rather was the supreme example of God’s love for us, and its purpose was to convince us to repent.[8]

Bernard of Clairvaux (1090 – 1153), a Cistercian monk and Doctor of the Church, opposed Abelard’s rejection of the expiatory nature of Jesus’s sacrifice and maintained the position that Christ’s cross did indeed have a sacrificial character before God. At the same time, St. Bernard drew upon Abelard’s emphasis on Christ’s love and the awakening of love in the believer, something that St. Anselm did not address in his explanation.

St. Thomas Aquinas, another Doctor of the Church, improved upon St. Anselm’s satisfaction theory in two ways. First, he says that God could have forgiven man without due satisfaction, but that it was most fitting for man that God forgave him through the death of Christ. This method was most fitting because it involved reparation and allows us to participate in the reparation.

Why was Jesus’s sacrifice most fitting?

How was Jesus’s sacrifice “most fitting”? Consider this analogy, keeping in mind that all analogies have their limits. Suppose a young boy, while playing baseball with his buddies, breaks his neighbor’s kitchen window with his ball. Now the neighbor could say to the boy, “Son, it’s okay. Don’t worry about a thing, try to forget it ever happened. That window means nothing to me.” Alternatively, he could say, “Son, I really want my window fixed, but I know that it’s impossible for you to pay to have the damage repaired and you don’t know even know how to fix a window. I’ll pay for the glass and repair the window myself. Walk with me down to the hardware store to get the supplies, and after that, you can help me while I fix the window.”

Which alternative would be most “fitting”, or be most consistent with the neighbor’s passion to make things right? The little boy’s help will probably not amount to much, but the kindly neighbor, through his sacrifice and generosity, is imbuing it with great meaning and purpose. In a limited way, this story shows a way in which Christ’s sacrifice was most fitting in the eyes of St. Thomas Aquinas. I would add that St. Thomas also maintained that it was not only the infinite dignity of God, but the love of God, that was the basis or driving principle of satisfaction.[9]

St. Thomas emphasized the fact that Christ’s death was both a gift of the Father and a self-offering on the part of the Son. To ignore Jesus’s self-offering, as I said earlier, indicates a flawed view of the Holy Trinity. St. Thomas Aquinas says,

“Christ as God delivered Himself up to death by the same will and action as that by which the Father delivered Him up; but as man He gave Himself up by a will inspired of the Father. Consequently there is no contrariety in the Father delivering Him up and in Christ delivering Himself up.”[10]

Summary

Jesus’s death was truly an expiatory sacrifice satisfying man’s infinite debt to God and was a matter of both justice and love. Only an infinite God could provide the infinite satisfaction. Only a man can satisfy since he caused the offense. The solution therefore is a God-man who as God can provide infinite satisfaction and as man can satisfy for man’s offense.[11] But this sacrifice, the sacrifice of the New Passover, was both a self-offering of Jesus and a gift of the Father and was based on God’s great love for us. While God could have saved us in another manner, this method was most fitting because it involved reparation and allows us to participate in the reparation. Secondarily, it models for us what it means to “die to self”, which is the essence of repentance and invites us to that repentance.

Do any of these reflections sound like “juridical and clumsy rationalizations” to you? Of course not. Kiko Arguello is wrong. Instead and together, they are an example of the Church’s slow and gradual exploration of the mystery of the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross. The great mysteries of our Faith are not impenetrable puzzles, never to be understood by men, but rather are wells of infinite depth giving life-giving water. Throughout the centuries holy men and women will draw water ever deeper from the well, without ever, at least on this side of eternity, reaching the bottom.

References

- Scriptural and Catechetical References, as well as teachings of the Ecumenical Councils of the Church: Click Here

- “Dictionary of Biblical Theology”, 2nd Edition, Edited by Xavier Leon-Dufour, The Word Among Us Press, 1988.

- “Understanding the Wrath of God”, Msgr. Charles Pope, http://blog.adw.org/2012/08/understanding-of-the-wrath-of-god/, retrieved August 31, 2014.

- St. Gregory of Nyssa’s Great Catechism, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2908.htm, retrieved August 31, 2014

- Independent Catholic University, Course in Christology, Lesson 11, http://icucourses.com/pages/037-11-salvation-theories-of-atonement, retrieved August 31, 2014

- Summa Theologica, 3rd Part, Question 47. St. Thomas Aquinas. http://www.newadvent.org/summa/4.htm, retrieved August 31, 2014

- Cur Deus Homo (“Why God Became Man”), St. Anselm of Canterbury, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/anselm-curdeus.asp, retrieved August 31, 2014

- Peter Abelard: The Cross and God’s Love, http://www.theologian-theology.com/theologians/peter-abelard-gods-love/, retrieved August 31, 2014.

- “Mere Christianity”, Chapter 4, “The Perfect Penitent”, C.S. Lewis, http://homepages.paradise.net.nz/mischedj/ca_lewisatone.html, retrieved August 31, 2014

- “Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma”, Dr. Ludwig Ott, Tan Books and Publishers, Inc., Rockford, Illinois, 1960.

Endnotes

[1] Vol. I of the Catechetical Directory, p 361.

[2] “Understanding the Wrath of God”, Msgr. Charles Pope, http://blog.adw.org/2012/08/understanding-of-the-wrath-of-god/, retrieved August 31, 2014.

[3] “Fundamentals of Catholic Dogma”, Dr. Ludwig Ott, p. 186.

[4] Matthew 20:28, 1 Timothy 2:5-6, and Revelation 5:9

[5] St. Gregory of Nyssa’s Great Catechism, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2908.htm, retrieved August 31, 2014

[6] St. Augustine’s Sermon cxxx, Part 2, http://www.ewtn.com/library/PATRISTC/PNI6-12.TXT, retrieved August 31, 2014.

[7] Cur Deus Homo (“Why God Became Man”), St. Anselm of Canterbury, http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/basis/anselm-curdeus.asp, retrieved August 31, 2014

[8] Independent Catholic University, Course in Christology, Lesson 11, http://icucourses.com/pages/037-11-salvation-theories-of-atonement, retrieved August 31, 2014

[9] Ibid.

[10] Summa Theologica, Third Part, Question 47, Article 3, http://www.newadvent.org/summa/4.htm, retrieved August 31, 2014

[11] Independent Catholic University, Course in Christology, Lesson 11, http://icucourses.com/pages/037-11-salvation-theories-of-atonement,

Tags: Camino Neocatecumal, Neocatechumenal Way

regarding Jesus’s sacrifice as expiation … the newest and most intriguing treatment i’ve read is pope benedict xvi’s excellent reflection on the greek word hilasterion, which he examines in volume ii of his masterful Jesus of Nazareth book trilogy. it’s the word st paul uses in romans 3:25 and which is usually translated as “expiation.”

i’ve been prayerfully thinking about benedict’s explanation, and i’ve found that it has helped me reconcile (…inadvertent pun…) not just the mystery of divine justice vs divine mercy, but also the necessity of purgatory, and even its consistency with natural physics, specifically perfect vs imperfect conductors. these may end up as just the wayward thoughts of my wandering mind 🙂 but i’ll keep praying over them.

I have the first book, Rey, now I know that I have to score the other two. Maybe for my birthday…

Thank you, Chuck, for your contributions on this and previous posts on your blog and on Tim’s as well. You have been instrumental in helping me understand the Church’s teaching, and helping me to confirm what I am learning as I read the/listen to the Divine Office(Liturgy of the Hours/app on my phone). I am especially grateful for learning about Kiko’s anti-Catholic doctrines and the explanations you share about these. They will assist me in refuting his beliefs if I am confronted by any of his Neos!