Is the Bible a science book? How should we react when we read things in the Bible that seem to contradict well established scientific facts? Let’s see what St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas had to say about the matter.

Three Principles

Sometimes the words of the Old Testament seem to contradict good science. Let’s consider three principles that will help us determine the literal sense of a particular scriptural passage. The literal sense is the meaning conveyed by the words of Scripture themselves and the sense intended by the inspired human author and provides the basis for the spiritual sense of scripture.

The first of the three principles is that everything in the Scriptures is ordered toward our salvation. The second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, Dei Verbum, section 11, states:

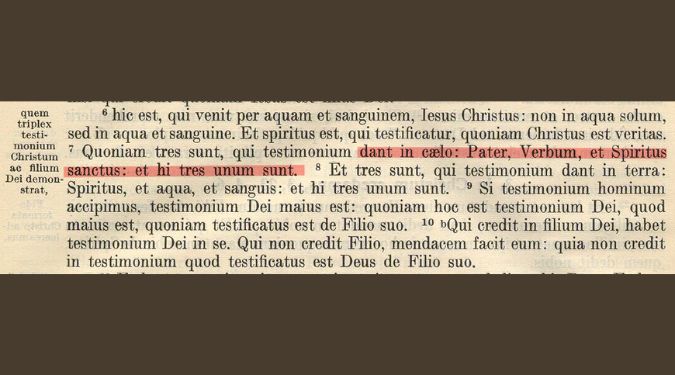

Therefore, since everything asserted by the inspired authors or sacred writers must be held to be asserted by the Holy Spirit, it follows that the books of Scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings for the sake of salvation.

Dei Verbum then quotes St. Paul’s second letter to Timothy, chapter 3, verses 16 and 17:

All scripture is inspired by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.

We agree with St. Paul wholeheartedly in this!

St. Augustine said, when discussing a description of the heavens found in the early chapters of the Book of Genesis:

But the credibility of Scripture is at stake, and as I have indicated more than once, there is danger that a man uninstructed in divine revelation, discovering something in Scripture or hearing from it something that seems to be at variance with the knowledge he has acquired, may resolutely withhold his assent in other matters where Scripture presents useful admonitions, narratives, or declarations. Hence, I must say briefly that in the matter of the shape of heaven the sacred writers knew the truth, but that the Spirit of God, who spoke through them, did not wish to teach men these facts that would be of no avail for their salvation.

St. Augustine, De Genesi ad Litteram, Book 2, Chapter 9, para. 20

So the Bible is not a science book and cannot be read as such. It’s a salvation book.

Secondly, the sacred writers described things as the senses perceived them.

The first chapter of the Book of Genesis describes the waters of the heavens and earth as being separated by a “firmament” or in the original Hebrew, a hammered bowl or vault. Speaking on this description of water in the Book of Genesis, St. Thomas Aquinas says:

As, however, this theory can be shown to be false by solid reasons, it cannot be held to be the sense of Holy Scripture. It should rather be considered that Moses was speaking to ignorant people, and that out of condescension to their weakness he put before them only such things as are apparent to sense.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, Question 68, Article 3

St. Thomas goes on to say that Moses, the presumed author of Genesis at that time, does this “to avoid setting before ignorant persons something beyond their knowledge.”

Pope Leo XIII corroborates this idea in his 1893 encyclical, Providentissimus Deus (“On The Study Of Holy Scripture”) when he speaks of the inspired authors of the Old Testament:

They did not seek to penetrate the secrets of nature, but rather described and dealt with things in more or less figurative language, or in terms which were commonly used at the time, and which in many instances are in daily use at this day, even by the most eminent men of science.

Pope Leo XII, Providentissimus Deus, 18

The inspired authors had no telescopes or microscopes.

A third principle is that the literal sense is not the literalist sense.

In 1993, the Pontifical Biblical Commission presented a document called “The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church” to Pope John Paul II. The Pontifical Biblical Commission had this to say about the literal sense of the Sacred Scriptures:

The literal sense is not to be confused with the “literalist” sense to which fundamentalists are attached. It is not sufficient to translate a text word for word in order to obtain its literal sense. One must understand the text according to the literary conventions of the time. When a text is metaphorical, its literal sense is not that which flows immediately from a word-to-word translation (e.g. “Let your loins be girt”: Lk. 12:35), but that which corresponds to the metaphorical use of these terms (“Be ready for action”).

The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church, II.B.1

That is, in order to determine the literal sense of a particular biblical text, it’s not enough to determine what the words themselves mean. One must ascertain the literary convention it uses, be it historical narrative, allegory, simile, metaphor, hyperbole, or poetry.

Conclusion

So we’ve heard three principles that can help us read the literal sense of the Scriptures with the Church:

- everything in the Scriptures is ordered toward our salvation;

- the sacred writers described things as the senses perceived them, not scientifically; and

- the literal sense is not the literalist sense.

In the next post we’ll take a look at St. Thomas Aquinas’s perspective on the creation story of the first chapter of Genesis.

This explains a lot!

Great piece!