Why have modern translations of the Bible removed a verse traditionally held to be part of the inspired Sacred Scriptures?

If one reads the 7th and 8th verses in the fifth chapter of the first letter of St. John from an old English translation of the Bible, such as the King James Version or the Challoner Revision of the Douay Rheims Bible, one sees:

And there are Three who give testimony in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost. And these three are one. And there are three that give testimony on earth: the spirit and the water and the blood. And these three are one. 1 John 5:7-8 Challoner Douay-Rheims

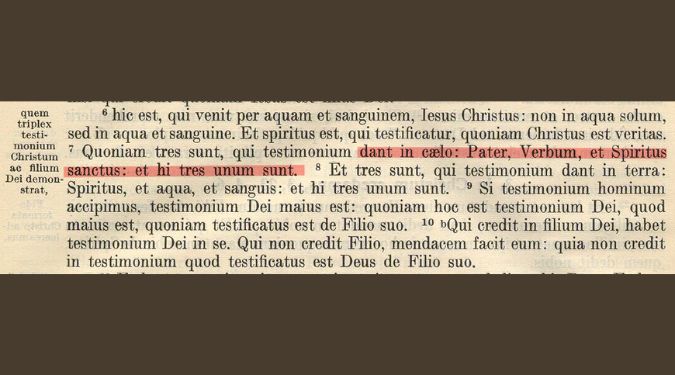

The same verses in the Clementine Vulgate are:

Quoniam tres sunt, qui testimonium dant in cælo: Pater, Verbum, et Spiritus sanctus: et hi tres unum sunt. Et tres sunt, qui testimonium dant in terra: Spiritus, et aqua, et sanguis: et hi tres unum sunt. 1 John 5:7-8 Clementine Vulgate

Newer translations of the New Testament, however, have removed some of the words traditionally held to be in those verses. For example:

So there are three that testify, the Spirit, the water, and the blood, and the three are of one accord. 1 John 5:7-8 NABRE

The missing words, called “the Johannine Comma” or the “Comma Johanneum” are, “in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost. And these three are one. And there are three that give testimony on earth”. In Latin, they are “dant in cælo: Pater, Verbum, et Spiritus sanctus: et hi tres unum sunt. Et tres sunt, qui testimonium dant in terra”.

Why has it been removed from modern translations?

The Johannine Comma is found in a handful of late Greek manuscripts, along with a few medieval Vulgate manuscripts and the Clementine Vulgate of 1592. (Hahn, Ph.D. and Mitch, M.A. 2224) It cannot be found in any New Testament manuscripts prior to the end of the 4th century and more manuscripts of the Latin Vulgate prior to AD 1200 lack it than have it. It does not appear in any extant copies of the Vulgate prior to AD 800. (Vawter, C.M. 411) The first two Greek translations of the New Testament produced by the scholar Erasmus lacked the Johannine Comma although he did include it into the 3rd edition of his Greek New Testament from the Vulgate (1522). It then found its way into the Textus Receptus (1633) and consequently into the King James Version and the Rheims translation of the New Testament. (Perkins 993)

Most significantly, however, the Johannine Comma was not quoted by any of the Church Fathers during the Trinitarian controversies of the early Church, e.g. at the Councils of Nicaea (AD 325), Constantinople (AD 381), Ephesus (AD 431), Chalcedon (AD 451) or later councils. It is not present in any of the ancient manuscripts of the New Testament other than Latin, including the Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Ethiopic, Arabic and Slavonic.

What is its origin?

The Johannine Comma might have originally been a gloss in an old Latin version of the New Testament that could have arisen as a margin note to the verses verse 7-8 regarding a Trinitarian interpretation of the verses. This gloss then could have made its way into the text itself through a scribal error. (Hahn, Ph.D. and Mitch, M.A. 2224)

A Trinitarian interpretation of the original verses of 1 John 5:7-8 appear in the writings of St. Cyprian of Carthage (A.D. 251) and St. Augustine of Hippo (A.D. 427). In St. Cyprian’s “De ecclesiae catholicae unitate” (“On the Unity of the Catholic Church §6”), (A.D. 251) we read:

The Lord says, “I and the Father are one;” and again it is written of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, “And these three are one.” (Blakeney 19)

Notice that St. Cyprian does not quote 1 John 5:7-8 with the Johannine Comma but certainly would have done so if he was convinced that the phrase appeared in those verses.

St. Augustine also provides a Trinitarian interpretation of the verses In his work, Contra Maximinum, book 2, chapter 22 §. 3 (A.D. 427). But again, he does so without the help of the Johannine Comma, which he certainly would have employed if he knew it to be included in St. John’s letter. (Perkins 993)

The earliest witness to the text in Latin is by Priscillian of Avila (ca. AD 380) or his disciple Instantius in a work entitled Liber Apologeticus. (Metzger 717)

What has the Church said?

On January 13, 1897, the Holy Office (now known as the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith) issued this decree:

To the question: “Whether it can safely be denied, or at least called into doubt that the text of St. John in the first epistle, chapter 5, verse 7, is authentic, which read as follows: ‘And there are three that give testimony in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost. And these three are one?’ “—the response was given on January 13, 1897: In the negative.

At this point, the faithful could not deny or cast into doubt that the text of the Johannine Comma belonged in the First Letter of John.

Thirty years later, on June 2, 1927, the same Holy Office “walked back” this decree quite a bit:

“This decree was passed to check the audacity of private teachers who attributed to themselves the right either of rejecting entirely the authenticity of the Johannine comma, or at least of calling it into question by their own final judgment. But it was not meant at all to prevent Catholic writers from investigating the subject more fully and, after weighing the arguments accurately on both sides, with that and temperance which the gravity of the subject requires, from inclining toward an opinion in opposition to its authenticity, provided they professed that they were ready to abide by the judgment of the Church, to which the duty was delegated by Jesus Christ not only of interpreting Holy Scripture but also of guarding it faithfully.” (Denzinger 569-570)

Catholic writers were then allowed to express their opposition to the authenticity of the Johannine Comma, provided that they would abide by any future judgment of the Church on the matter.

That future judgment came in 1979 with the promulgation of the Nova Vulgata (New Vulgate) by St. Pope John Paul II:

“…the old text of the Vulgate edition was taken into consideration word for word, namely, whenever the original texts are accurately rendered, such as they are found in modern critical editions; however the text was prudently improved, whenever it departs from them or interprets them less correctly. For this reason Christian biblical Latinity was used so that a just evaluation of tradition might be properly combined with the legitimate demands of critical science prevailing in these times.“ (Scripturarum Thesaurus | St. John Paul II)

In the promulgation of the Nova Vulgata, the Church ruled, at least implicitly, on the Johannine Comma by removing it from the text:

Quia tres sunt, qui testificantur: Spiritus et aqua et sanguis; et hi tres in unum sunt. 1 John 5:7-8 Nova Vulgata

Works Cited

Nova Vulgata – Bibliorum Sacrorum Editio, The Holy See, https://www.vatican.va/archive/bible/nova_vulgata/documents/nova-vulgata_index_lt.html. Accessed 22 February 2025.

Blakeney, E. H., translator. Cyprian De unitate ecclesiae. New York, The Macmillan Co., 1928.

Denzinger, Heinrich. The Sources of Catholic Dogma. Translated by Roy Joseph Deferrari, Loreto Publications, 2001.

Hahn, Ph.D., Scott, and Curtis J. Mitch, M.A., editors. The Ignatius Catholic Study Bible. San Francisco, Ignatius Press, 2024.

Metzger, Bruce M. A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament. London, United Bible Societies, 1971.

Perkins, Pheme. “The Johannine Epistles.” The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, edited by Raymond Edward Brown, et al., Prentice-Hall, 1990, pp. 986-995.

Scripurarum Thesaurus | St. John Paul II. Apostolic Constitution. 25 April 1979, Rome. The Holy See, https://www.vatican.va/content/john-paul-ii/en/apost_constitutions/documents/hf_jp-ii_apc_19790425_scripturarum-thesaurus.html. Accessed 14 December 2024.

Vawter, C.M., Bruce. “The Johannine Epistles.” The Jerome Biblical Commentary, edited by Raymond E. Brown, S.S., et al., Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1968, pp. 404-413.