Introduction

Upon picking up and perusing the Gospel of Mark we’ll immediately notice two things. First, it is considerably shorter than the other gospels, perhaps only half as long and can be read aloud in less than two hours. Second, it seems to be “missing” narratives of the birth and infancy of Jesus that we see in the other synoptic gospels, i.e. Matthew and Luke. Further study has led many to conclude that the Gospel of Mark has a certain symmetric structure and that beginning his gospel with the baptism of Jesus allowed him to link that event with Jesus’s Passion and Resurrection. These observations have led some scholars to conclude that Mark’s gospel was read aloud to candidates preparing for baptism, likely on the Vigil of Easter (Standaert 9). To borrow a secular term, Mark wrote his gospel for a rhetorical purpose – to persuade people of something.

Rhetorical Analysis

Mark had much material to work with, which in many cases was passed down to him orally and traditionally from Peter (Hendrickx, From One Jesus, 59). He had the sacred duty to pick and choose which material to include in his writing.

Because the original gospels contained no punctuation, paragraph breaks, chapters or verse designations, the sacred authors like Mark deployed various literary devices and imbued their works with a structure of some type (Breck 59). Studying these rhetorical elements can lead us to a deeper understanding of the inspired writer’s message and purpose. Indeed, the Pontifical Biblical Commission has spoken approvingly of this approach (Catholic Church. Pontificia Commissio Biblica 44):

Other exegetes concentrate upon the characteristic features of the biblical literary tradition. Rooted in Semitic culture, this displays a distinct preference for symmetrical compositions, through which one can detect relationships between different elements in the text. The study of the multiple forms of parallelism and other procedures characteristic of the Semitic mode of composition allows for a better discernment of the literary structure of texts, which can only lead to a more adequate understanding of their message.

The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church: Address of His Holiness Pope John Paul II and Document of the Pontifical Biblical Commission.

Chiasmus and Inclusio

What are some of the symmetrical structures and parallelism present in the Sacred Scriptures?

One is “chiasmus” (also referred to as a chiasm), “a literary device in which ideas are presented and then subsequently repeated or inverted in a symmetrical mirror-like structure.” (Ryan). The word “chiasm” is derived from a Greek word meaning “to mark with a chi (X) (Gove 386). Chiasms vary in scale from word order in verses to the arrangement of verses and passages and can encompass an entire book, which we’ll soon see. These devices serve to focus our attention on the sacred author’s intention (Breck 2).

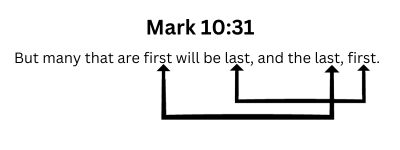

Here is an example of chiasmus in a verse:

Another structural device is “inclusion” or “inclusio”, which is the framing of a passage or section by placing identical or similar phrases or verses at the beginning and the end of the passage or section (Breck 2). In the Gospel of Mark we find examples of inclusio as well as that of chiastic form.

The Gospel of Mark

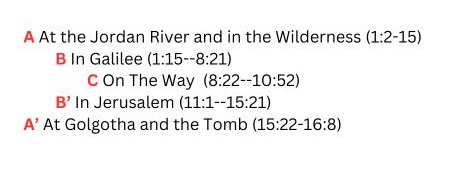

Scholars have noticed that the book has a five-fold chiastic structure based upon location (Hendrickx, Key to the Gospel, 5). The opening scene of the gospel is set at the Jordan River in the wilderness, and then moves to Galilee. From there, Jesus and his apostles set about on “the Way”, and eventually enter Jerusalem. The gospel ends outside the walls of Jerusalem at Golgotha and then the tomb. In using a concentric parallelism, Mark effectively highlights his chief themes in the very center of his work.

Here is a high-level outline of this concentric parallelism in the Gospel of Mark:

“On the Way” is the central part of the gospel; the Jordan and the Wilderness is matched with Golgotha and the Tomb; and Galilee is contrasted with Jerusalem. While the Church holds that the passages after 16:8 are canonical and inspired, there is a consensus among scholars that this gospel originally ended with verse 16:8 (Lohse, 134).

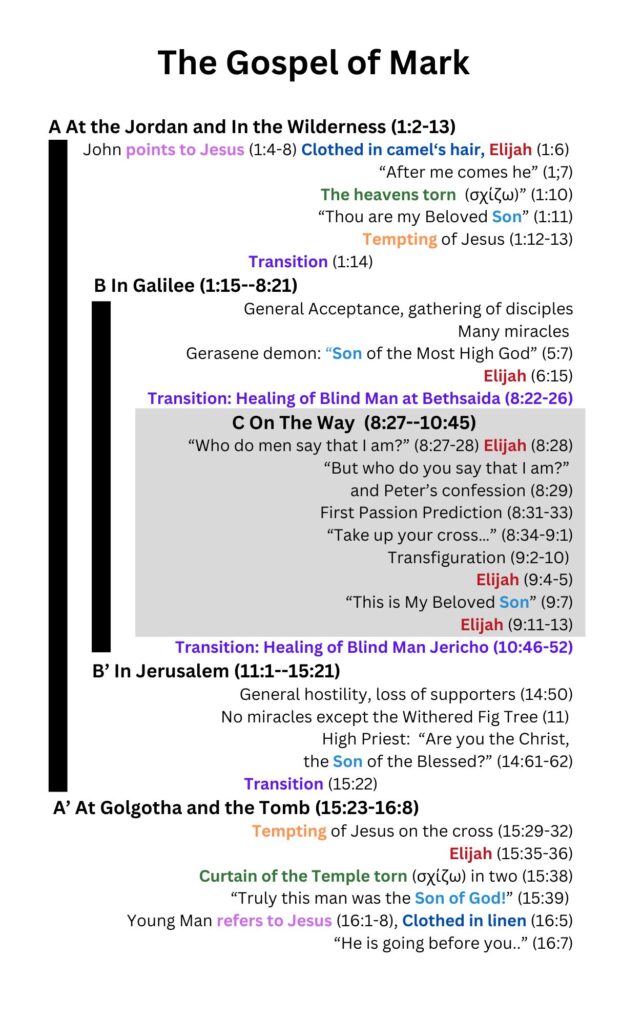

The Jordan &Wilderness/Golgotha & the Tomb

The wilderness, Golgotha and the tomb are desolate, lonely places. John points to or refers to Jesus at the Jordan River, as does the young man at the Tomb. John is clothed with camel’s hair and leather girdle (1:6), while the young man at the Tomb is clothed in linen (16:5). John says, “after me comes he”, while the young man at the Tomb says, “He is going before you.” (Krantz 3) At Our Lord’s baptism in the Jordan, the heavens were torn open (1:10), while at Golgotha, the veil of the Temple split (15:38). In both sections, a form of the Koine Greek word σχίζω (pronounced SKHID’-zo), which means “torn, split, or cleave“, is used (Krantz 4). In these ways, Mark links baptism and the Passion and Resurrection of our Lord in that the heavenly sanctuary is opened for His disciples.

The prophet Elijah is referenced or alluded to at the Jordan and at Golgotha. At the Jordan, God speaks from heaven, “Thou are my Beloved Son” (1:11) and at Golgotha, the centurion says, “Truly this man was the Son of God!” (15:39). Lastly, Jesus is tempted in the wilderness (1:12-13) and at Golgotha He was tempted with taunts (15:29-32) (Krantz 7).

Galilee/Jerusalem

Jesus leaves the wilderness and begins his ministry in Galilee in 1:14. Mark contrasts Galilee to Jerusalem in a powerful use of concentric parallelism or chiastic form. Galilee is a faraway province on the periphery, while Jerusalem is the seat of political and religious power. In Galilee, Jesus is widely and enthusiastically accepted (with a few exceptions), and gathers his disciples. See 1:22,33; 2:2,12; 3:7; 4:1; 5:21,23; 6:31-34, 54-56; and 7:37-8:1. In Jerusalem, Jesus faces general hostility (11:18; 12:12; 14:1,10 ) and loses supporters (14:50). Most of His few opponents in Galilee came from Jerusalem (3:22, 7:1). Jesus performed many miracles in Galilee, but only performed the miracle of the withered fig tree in the environs of Jerusalem (11:12-14, 20-26).

On the Way

But Jesus does not stay in Galilee. After healing a blind man at Bethsaida (north of the Sea of Galilee on the east side of the Jordan River), he and his apostles set out “on the Way”. This section, which runs from 8:22-10:52, is the central section of the Gospel and with the exception of a secret visit to Galilee (9:30ff) is set in neither Galilee nor in Jerusalem. It is marked by seven uses of the word ὁδός (hodos, pronounced hod-OS), which means a way, a journey, or a path (8:27; 9:33,34; 10:17,32, 46) (Hendrickx, Key to the Gospel, 17). By the way, ὁδός, the Way, is used in the book of the Acts of the Apostles as a name for the Church. (Acts 9:2; 22:4; 24:14, 22).

It is in this central section that Mark packs his punch and relates events that reveal the fullness of Our Lord’s identity. He first asks his apostles, “Who do men say that I am?” (8:27-28) He then asks, “But who do you say that I am?” At this point Peter answers, “You are the Christ.”, marking the first time in the Gospel that a person realizes Our Lord’s true identity as the Messiah. There is a general consensus that this is a turning point in the Gospel as it pivots to the Passion. Indeed, Jesus answers Peter with His first prediction of His Passion: “the Son of man must suffer many things, and be rejected by the elders and the chief priests and the scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again.” (8:31-33)

Jesus soon says something very shocking: “If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me.” (8:34). We’re accustomed today to think of “our cross” as the burdens we carry in life, and while this is true, we must remember that to His original listeners the cross was an implement of a bloody, horrific, and humiliating method of execution.

Following this, Mark relates the Transfiguration of our Lord (9:2-10), where Peter, James, and John get a glimpse of Jesus’s future glory and God says, “This is My Beloved Son” (9:7)

The “On the Way” section ends with Jesus healing the blind man, Bartimaeus, at Jericho (10:46-52), which forms an “inclusio” with the healing of the blind man that preceded the section. These very real healings indicate to us that it is Jesus who opens our spiritual eyes to perceive His true identity (Hendrickx, From One Jesus, 65).

Jesus then enters Jerusalem and the drama of the Passion commences.

Confirmations of His Identity

Confirmations of our Lord’s identity occur throughout Mark’s gospel. In the first half of the gospel, people regularly ask “Who is this?” (1:27; 2:7-12; 4:41; 5:17; 6:2-3,14-16) (Hendrickx, Key to the Gospel, 14-15), and Jesus commands demons, the cured, and his apostles to keep signs of his true identity secret (1:25,34, 44; 3:12; 5:43; 7:36-37; 8:26,30; and 9:9). (The Navarre Bible: New Testament in the Revised Standard Version and New Vulgate 159)

The prophet Malachi said that Elijah would reappear before the Day of the Lord (Mal. 3:2-3; 4:5-6), and there are references to or allusions to the prophet Elijah in all of the settings except Jerusalem. John the Baptist baptized at the Jordan near the place where Elijah departed into heaven (1:5; 2 Kings 2:6-11) and wore the same clothing as Elijah (1:6; 2 Kings 1:8). On the Way, Elijah and John the Baptist were linked in the minds of the people listening to Jesus (8:27-28) and Elijah appeared at the Transfiguration (9:4-13). On the Way, our Lord himself makes clear that John the Baptist served the role of Elijah (9:11-13). At Golgotha, bystanders mistakenly thought that Jesus was calling on Elijah from the cross (15:35-36).

Our Lord is identified as the Son of God in in all five sections of the book. At the Jordan and on the Way, it is God himself who pronounces this (1:11, 9:7). In Galilee, it is the demons who proclaim it (3:11-12; 5:7). In Jerusalem, the high priest pointedly asks Jesus if he is the “Son of the Blessed”, and Jesus definitively replies, “I am.” (14:61-62) At Golgotha, a centurion proclaims, “Truly this man was the Son of God!” (15:39).

Over and above the many healing miracles described in the book, and to dispel any doubt that being the “Son of God” meant that He was divine, Jesus assumes the prerogatives of God four times in this gospel (Scott 20-23). In Galilee He forgives sins (2:10) and commands the wind and sea (4:40). On the Way, he associates himself with the goodness of God (10:19) and in Jerusalem He claims God’s eschatological power (14:62). He is accused of blasphemy in the first and last of these incidents (2:7; 14:64).

Conclusion

While our discussion here does not exhaust the riches of the Gospel of Mark, it does show how Mark uses a certain literary structure, namely a symmetric chiastic form, in the service of evangelism. Mark had a sacred purpose which was not merely to tell the story of Jesus of Nazareth, but to persuade men and women to follow Him. In a word, his purpose is “conversion,” and the prerequisite for understanding our Lord’s teaching in this gospel is understanding who He is. His gospel reveals our Lord’s full identity and challenges disciples with the same question that Jesus posed to his apostles, “But who do you say that I am?” Mark attempts to persuade us to accept Jesus as the powerful Son of God, the Messiah who nevertheless had to suffer, die and then be glorified – a way that must be followed by his true disciples.

Here is a chart that summarizes some of our discussion:

Works Cited

Breck, John. The Shape of Biblical Language: Chiasmus in the Scriptures and Beyond. St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1994.

Catholic Church. Pontificia Commissio Biblica. The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church: Address of His Holiness Pope John Paul II and Document of the Pontifical Biblical Commission. Boston, Pauline Books & Media, 1999.

Gove, Philip Babcock, editor. Webster’s Third New International Dictionary of the English Language. Springfield, MA, Merriam-Webster, Inc., 1993.

Hendrickx, Herman. From One Jesus to Four Gospels. Maryhill School of Theology, 1991.

—. Key to the Gospel of Mark. Quezon City, Philippines, Maryhill School of Theology, 1993.

Krantz, Jeffrey H. Crucified Son of Man or Mighty One?: Mark’s Chiastic Gospel Structure and the question of Jesus’ identity.

Larsen, Kevin W. “The Structure of Mark’s Gospel: Current Proposals.” Currents in Biblical Research, vol. 3, no. 1, 2004, pp. 140-160.

Lohse, Eduard. The Formation of the New Testament. Abingdon, 1981.

Lusk, Rich. “Symmetry and Structure in the Gospel of Mark.” YouTube, Theopolis Institute, 18 November 2016, https://youtu.be/xQRsVJTdRSY. Accessed 30 December 2023.

The Navarre Bible: New Testament in the Revised Standard Version and New Vulgate. Four Courts Press, 2008.

Ryan, Joel. “What Is Chiasmus? Definitions and Examples of Chiastic Structure in the Bible.” Christianity.com, 28 August 2019, https://www.christianity.com/wiki/bible/what-is-chiasmus-definitions-and-examples.html. Accessed 22 December 2023.

Scott, M. Philip. “Chiastic Structure: A Key to the Interpretation of Mark’s Gospel.” Biblical Theology Bulletin: Journal of Bible and Culture, vol. 15, no. 1, 1985, pp. 17-26.

Standaert OSB, Benoit. L’Evangile Selon Marc: Composition et Genre Litteraire. Dissertation. 24 April 1978, p. 678.