“But I say to you, Do not resist one who is evil. But if any one strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also” Mt. 5:39

By his words and example, did Jesus teach us to be completely passive in our personal encounters with evil?

Most teachers of passivity purport to draw from two sources for such an interpretation of our Lord’s teaching: The “Suffering Servant” narratives in Isaiah 53, and the Sermon on the Mount (Mt. 5-7).

The Suffering Servant

The teaching of passivity is based, in great part, on The Suffering Servant (the Servant of YHWH) in Isaiah 53:

“He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth; like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is dumb, so he opened not his mouth.” Isaiah 53:7

The Church has long considered the rich, prophetic symbolism of the Suffering Servant narratives to be a prefiguring, or prophesy, of the Passion of Christ. It is wrong, however, to apply this text thoughtlessly to the entirety of Christ’s public ministry, or even uncritically to Christ’s passion. For example, our Lord was not exactly silent when on trial in front of the High Priest, and especially when he was struck by one of the high priest’s officers:

“Jesus answered him, “I have spoken openly to the world; I always taught in synagogues and in the temple, where all the Jews come together; and I spoke nothing in secret. Why do you question Me? Question those who have heard what I spoke to them; they know what I said.” When He had said this, one of the officers standing nearby struck Jesus, saying, “Is that the way You answer the high priest?” Jesus answered him, “If I have spoken wrongly, testify of the wrong; but if rightly, why do you strike Me?” John 18:20-23

The Sermon on the Mount

Others arrive at a passive interpretation of “Do not resist evil” from some words spoken by our Lord in the Sermon on the Mount. Let’s consider these words:

“You have heard that it was said, ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say to you, Do not resist one who is evil. But if any one strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also; and if any one would sue you and take your coat, let him have your cloak as well; and if any one forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles. Give to him who begs from you, and do not refuse him who would borrow from you.” Mt. 5:38-42

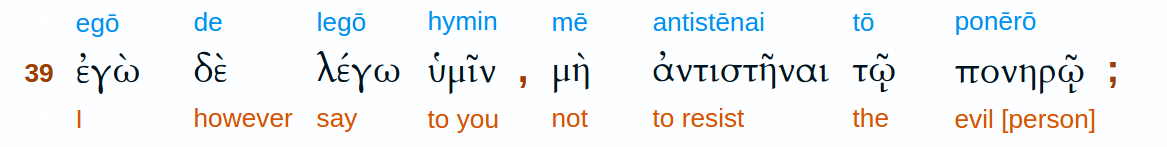

Consider the first part of verse 39: “But I say to you, Do not resist one who is evil.”

Here is the verse in the original Koine Greek:

We can get to the heart of the matter by considering the word St. Matthew uses for “resist”, which is the Greek word, “antistenai”.

New Testament scholar Walter Wink, in his book, “Jesus and Nonviolence, A Third Way” [p.11], says:

“The Greek word is made up of two parts: anti, a word still used in English for “against,” and histēmi, a verb that in its noun form (stasis) means violent rebellion, armed revolt, sharp dissention. In the Greek Old Testament, antistēnai is used primarily for military encounters—44 out of 71 times. It refers specifically to the moment two armies collide, steel on steel, until one side breaks and flees.”

St. Paul also uses the same word, “antistenai”, in the sixth chapter of his letter to the Ephesians. There he uses a dramatic military metaphor to urge the Ephesians to resist evil, but with the armor and weapons of God:

“Therefore, put on the armor of God, that you may be able to resist [antistenai] on the evil day and, having done everything, to hold your ground [stenai].” Ephesians 6:13 [1]

An accurate translation of Matthew 5:39a, would then be, “Do not respond in kind to those who do evil to you.” That vastly differs from the phrase, “Do not resist evil”, in that it allows and even invites us to vigorously and creatively respond to evil in our personal encounters with it, albeit nonviolently.

On a side note, we also see see that the direct object of verse 39a is not the generic, unspecific “evil” in “Do not resist evil,” but rather, “do not resist the evil person.”

Peter and Paul Weigh In

Saints Peter and Paul confirm this interpretation. For example, read St. Paul’s summary of the Sermon on the Mount in the 12th chapter of his letter to the Romans:

“…Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave it to the wrath of God; for it is written, “Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.” No, “if your enemy is hungry, feed him; if he is thirsty, give him drink; for by so doing you will heap burning coals upon his head.” Romans 12:19-20

and from the First Letter of Peter:

“Do not return evil for evil or reviling for reviling; but on the contrary bless, for to this you have been called, that you may obtain a blessing.” 1 Peter 3:9

In other words, in response to evil, we are not to do evil, we are not to retaliate, we are not to seek revenge, we are not to revile, and we are to have mercy on the enemy. Our Lord places no restriction on us whatsoever, however, from pursuing justice and defending our lives.

“Turn the other cheek…”

In his public ministry, Jesus often pushed people from their comfort zones into places from which the only means of escape was some serious soul-searching. It is not surprising, then, that he taught that form of non-violent response to the lowly and oppressed who followed him. Do not forget his advice to his disciples, “Behold, I send you out as sheep in the midst of wolves; so be wise as serpents and innocent as doves [Mt. 10:16].”

Our Lord give three specific examples to the poor people listening to him on the mountain: “Turn the other cheek,” “let him have your cloak as well,” and “go with him two miles.” Each example gave those who were listening a way to resist evil without resorting to violence. Let’s consider each in turn.[2]

“if any one strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also…”

Did you ever wonder why Jesus explicitly mentioned the right cheek? How does one, in the right-handed world of first century Palestine, where the use of one’s left hand was often taboo, strike another on the right cheek? With a right-handed back slap, of course. Jesus was speaking directly to a poor, downtrodden and colonized people, and a back slap was a humiliating action of a master toward a slave, of a Roman to a Jew, of a landowner to a tenant farmer. It was meant to degrade. Now, after having been slapped on the right cheek by a superior’s right hand, presenting the left cheek would effectively force the master to backslap again using his left hand, which was taboo, or to strike with his right fist, which would be the act of a peer, not a master. So, while risky, presenting the left cheek after a back slap would help the oppressed person recover a bit of his God-given dignity without having to resort to violence.

“If any one would sue you and take your coat, let him have your cloak as well…”

In the debtor society of first century Palestine, the lowly and landless did not sue each other, but rather, could be sued by the powerful. To take off the second and last piece of clothing in the public court of that time would make one naked, but the greater shame and embarrassment would not be born by the person being sued, but rather, the wealthy person suing him. Remember the great length to which Noah’s sons, Shem and Japheth went to in order to avoid the shame of seeing their father naked. [Gen. 9:23].

“If any one forces you to go one mile, go with him two miles…”

It would not have been uncommon for those listening to Jesus on the mountain – the men at least – to have been forced to carry the gear of a Roman legionary or an auxiliary for up to a mile. It was generally frowned upon, if not forbidden, for a legionary to require a colonized person to carry such a pack for more than that distance, and in fact, this was eventually codified into law. So, by cheerfully “going the extra mile”, one would place the legionary or auxiliary in the uncomfortable position of possibly facing disciplinary action by his superiors. The soldier would probably prefer to get his pack back, but how on earth would he ask for it back without losing his pride?

Examples from the Scriptures

The words of Our Lord’s Sermon on the Mount do not repudiate His own examples of resisting evil, or the examples set by heroes of the Old Testament.

Jesus resisted the evil of Satan in the desert [ Mt. 4:1-11]; he resisted the evil of the men who would stone the woman caught in adultery [John 8:1-11]; he drove the merchants and their animals from the temple [Mt. 21:12]; and he resisted the evil of the Pharisee’s disciples who would trap him with the question, “Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar, or not?” [ Mt. 22:15-22].

St. Paul Resisted Evil

St. Paul used his Roman citizenship to escape an evil beating and to appeal the case against him to the governors Felix and Festus, and ultimately to Caesar [Acts 22-24]. He defended himself in front of King Agrippa [Acts 26], and he even plotted a clever escape from the evil plans of his adversaries in Damascus [Acts 9:25] by having himself lowered from the city walls in a basket.

The Heroes of the Old Testament Resisted Evil

In the Old Testament, the Hebrew midwives Shifrah and Puah resisted the evil command of Pharaoh to murder Hebrew baby boys [Exodus 1:15-20]. The people of Israel boldly asked the Egyptians for reparations before leaving Egypt. [Exodus 12:35-36]. Shadrach, Meshach, and Abed′nego refused to worship the image that King ebuchadnez′zar had set up and so were thrown into the fiery furnace [Daniel 3]. Daniel resisted the evil order of King Darius to pray to him alone, and was consequently thrown into the lion’s den [Daniel 6:10-28]. Queen Esther risked her life and broke the law to approach the King Ahasuerus on behalf of her people, whose annihilation had been ordered [Esther 4-5]. And the priests of Nob lost their lives for resisting the evil of Saul by giving the consecrated bread to David and his men to eat [1 Samuel 21-22].

The Teaching of the Church

We read in the Catechism of the Catholic Church:

“The legitimate defense of persons and societies is not an exception to the prohibition against the murder of the innocent that constitutes intentional killing. “The act of self-defense can have a double effect: the preservation of one’s own life; and the killing of the aggressor. . . . The one is intended, the other is not. [CCC 2263]

and

“Love toward oneself remains a fundamental principle of morality. Therefore it is legitimate to insist on respect for one’s own right to life. Someone who defends his life is not guilty of murder even if he is forced to deal his aggressor a lethal blow…Nor is it necessary for salvation that a man omit the act of moderate self-defense to avoid killing the other man, since one is bound to take more care of one’s own life than of another’s.” [CCC 2264]

and

“Legitimate defense can be not only a right but a grave duty for one who is responsible for the lives of others. The defense of the common good requires that an unjust aggressor be rendered unable to cause harm.” [CCC 2264]

Conclusion

It is clear that in his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus teaches that we are not to resort to violence, retaliation, or revenge in our personal encounters of the evil of others. In short, we are to resist evil in a way that prevents us from becoming evil ourselves.

Endnotes

[1] Wink elaborates more on this in his book,”Engaging the Powers: Discernment and Resistance in a World of Domination“,(Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 1984) p. 185:

“What the translators have not noted, however, is how frequently anthistemi is used as a military term. Resistance implies “counteractive aggression,” a response to hostilities initiated by someone else. Liddell-Scott defines anthistemi as to “set against esp. in battle, withstand.” Ephesians 6:13 is exemplary of its military usage: “Therefore take up the whole armor of God, so that you may be able to withstand [antistenai, lit., to draw up battle ranks against the enemy] on that evil day, and having done everything, to stand firm [stenai, lit., to close ranks and continue to fight].” The term is used in the LXX primarily for armed resistance in military encounters (44 out of 71 times). Josephus uses anthistemi for violent struggle 15 out of 17 times, Philo 4 out of 10. As James W. Douglass notes, Jesus’ answer is set against the backdrop of the burning question of forcible resistance to Rome. In that context, “resistance” could have only one meaning: lethal violence.-16 In short, antistenai means more in Matt. 5:39a than simply to “stand against” or “resist.”” It means to resist violently, to revolt or rebel, to engage in an insurrection.”

[2] See “Jesus and Nonviolence, a Third Way“, by Walter Wink, Fortress Press, Minneapolis, 2003, pp 14-27.