In this post we’ll see how certain provisions of the Mosaic law prefigure a key principle of the Church’s Social Teaching, the Universal Destination of Goods.

Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Catholic Doctrine states this principle quite succinctly:

“Each human person is God’s creature and was intended by God to receive his necessary share of created goods.”

This definition is based upon magisterial teaching, including the teaching of the Second Vatican Council’s Pastoral Constitution on The Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes):

“God intended the earth with everything contained in it for the use of all human beings and peoples. Thus, under the leadership of justice and in the company of charity, created goods should be in abundance for all in like manner….the right of having a share of earthly goods sufficient for oneself and one’s family belongs to everyone.”

Gaudium et Spes, 69

At least three provisions of the Mosaic law prefigure the principle of the Universal Destination of Goods, and they each do so by guaranteeing each Israelite family a sufficient stake in the Promised Land on which to live.

The Daughters of Zelo’phehad

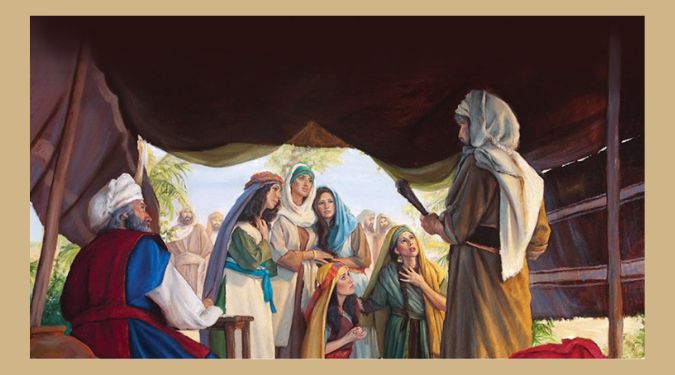

One story from the 27th chapter of the book of Numbers, that of the daughters of Zelo’phehad, is particularly illustrative:

Then drew near the daughters of Zelo′phehad (pronounced Tsel OFF heh chawd)…and they stood before Moses, and before Elea′zar the priest, and before the leaders and all the congregation, at the door of the tent of meeting, saying, “Our father died in the wilderness; he was not among the company of those who gathered themselves together against the Lord in the company of Korah, but died for his own sin; and he had no sons. Why should the name of our father be taken away from his family, because he had no son? Give to us a possession among our father’s brethren.”

Numbers 27:1-4

Many might conclude that these women were standing up for their rights, but in truth, they were trying to prevent their descendants from being alienated from the Promised Land.

As we discussed the the post, A Biblical Case for Clerical Celibacy, each family in Israel was promised a small share of the promised land. See Numbers 26:52-55. The promised land was to be divided between the tribes, then the clans, then families within the clans. This portion would be handed down to succeeding generations, and usually passed from father to sons. Joshua and Eleazar were given the job of coordinating the dividing of the land.

We see an example of how important this apportioning was to the Israelites in the First Book of Kings when Naboth refused to sell a plot of land to the evil king Ahab, saying:

“The Lord forbid that I should give you the inheritance of my fathers.”

1 Kings 21:3

We pick the story of the daughters of Zelo′phehad back up in the 27th chapter of the Book of Numbers:

Moses brought their case before the Lord. And the Lord said to Moses, “The daughters of Zelo′phehad are right; you shall give them possession of an inheritance among their father’s brethren and cause the inheritance of their father to pass to them. And you shall say to the people of Israel, ‘If a man dies, and has no son, then you shall cause his inheritance to pass to his daughter. And if he has no daughter, then you shall give his inheritance to his brothers. And if he has no brothers, then you shall give his inheritance to his father’s brothers. And if his father has no brothers, then you shall give his inheritance to his kinsman that is next to him of his family, and he shall possess it. And it shall be to the people of Israel a statute and ordinance, as the Lord commanded Moses.’”

Numbers 27:5-11

The purpose of this inheritance or portion was to prevent Israelites from being alienated from the Promised Land and returning to the kind of poverty and oppression they faced in Egypt.

The Mosaic Law had at least two other provisions that bolstered this protection.

Levirate Marriage

First, while marriage was forbidden between close relations (Leviticus 18:6–18), the Law of Levirate Marriage, which is Latin for “brother-in-law”, encouraged a brother to marry the widow of his brother in order to provide him with offspring and to continue his name. This is described in the 25th chapter of the book of Deuteronomy. If no brother survived, the nearest relative could assume the responsibility, as we see in the Book of Ruth.

The Year of Jubilee

Another provision which protected Israel from alienation was the Year of Jubilee. The jubilee was a “year of liberty” for Israel that was to occur every fiftieth year according to Leviticus 25:8–10. In the fiftieth year, on the Day of Atonement, all Israelites could reclaim their ancestral land. The Jubilee prevented the permanent sale of land, so the price of land was based on the number of harvests it would yield before the Jubilee (Leviticus 25:13-17). In today’s terms we would call this a type of long term lease.

Conclusion

As I stated earlier, these provisions of the Mosaic law prefigure the principle of the Universal Destination of Goods, and they do so by guaranteeing each Israelite family a sufficient stake in the Promised Land on which to live.

In 1891, Pope Leo XIII implied this in his landmark encyclical on Catholic Social Teaching, Rerum Novarum, when, in defending the right of ownership of private property, he said,

It is a most sacred law of nature that a father should provide food and all necessaries for those whom he has begotten; and, similarly, it is natural that he should wish that his children, who carry on, so to speak, and continue his personality, should be by him provided with all that is needful (emphasis added) to enable them to keep themselves decently from want and misery amid the uncertainties of this mortal life. Now, in no other way can a father effect this except by the ownership of productive property, which he can transmit to his children by inheritance.

Rerum Novarum, 13

One hundred years later, in his encyclical Centesimus Annus, St. Pope John Paul II wrote,

The original source of all that is good is the very act of God, who created both the earth and man, and who gave the earth to man so that he might have dominion over it by his work and enjoy its fruits (Genesis 1:28). God gave the earth to the whole human race for the sustenance of all its members, without excluding or favoring anyone. This is the foundation of the universal destination of the earth’s goods. The earth, by reason of its fruitfulness and its capacity to satisfy human needs, is God’s first gift for the sustenance of human life.

Centesimus Annus, 31

The Universal Destination of Goods is definitely not socialism or communism. First, there are no guarantees that one family will be as wealthy as their neighbors. Secondly, the Church teaches that the Universal Destination of Goods should be implemented through the principle of subsidiarity, that is, human needs should be met and addressed at the lowest and simplest level possible – first and foremost in the family, then the community, then state, then nation. The higher levels are to serve the family, not vice versa.

At the foundation of this subsidiarity is a personal responsibility on our part. As St. James tells us:

“If a brother or sister is ill-clad and in lack of daily food, and one of you says to them, “Go in peace, be warmed and filled,” without giving them the things needed for the body, what does it profit? So faith by itself, if it has no works, is dead.”

James 2:15-17

The Church has reflected on these issues in the light of the Gospel deeply for a long, long time. In the year ahead we’ll address many of the principles of Catholic Social Teaching in depth.